Faith in the Language of the Quilt

On Quilting, Rigidity, and the Miracles That Take Shape

I entered the quilting world with a thick vein of snobbery running through my bones. I felt a magnetic pull to quilt, but as I would approach it, I was repelled. It felt dead. Lifeless. I thought it was stuck in the past, full of bad taste and obsessive, anxious women. It took me quite some time to recognize that it wasn’t them but me that felt dead, rigid, lifeless, and full of bad taste. I was an obsessive, anxious woman. My cynicism blinded me to my own involvement. The quilting world wasn’t what was stuck creatively, I was.

I learned this attitude early. I graduated high school in 1993, during the supreme era of the cynic. In the 90s, our snobbery made us feel better about ourselves for “seeing behind the curtain.” We didn’t just reject tradition—we rejected anything that felt structured, rule-bound, or institutional. Bureaucracy, public systems, formal processes—these all felt like traps, designed to stifle rather than create. Quilting, with its rigid-seeming blocks and intricate rules, looked like another lifeless institution, something that had been codified and drained of spontaneity. Gen X and Gen Z are generational twins with our mutual love of thrifting, the grunge aesthetic, normcore staples, and baggy fits. We twin cynicism too.

If something felt too structured, too established, too bound by the past, we dismissed it. I unconsciously carried this belief into my creative life, treating tradition as stagnation rather than possibility. Quilting, like public systems and formal structures, felt like a bureaucracy of fabric—a set of rules that had already been decided, leaving little room for originality and freedom. And that resistance didn’t just shape how I saw quilting—it shaped how I saw my place in any structured system, from art to community to career.

My friends and me, 1994. I wore holes into that Captain America shirt that year.

I am not sure why I had picked quilting but my desire to make quilts never faltered. My cynicism told me quilting was stale, but my artistic instincts kept pulling me back. What I actually feared—structure, patterns, rules—was what I also loved. If I considered veering away from this style of quilting I grew less interested. I couldn’t abandon my project or get too close to it.

I love structure - my favorite artists from the grids of Agnes Martin, the conceptual instructions of Sol Lewitt, and the assemblages of Louise Nevelson all work magic with tight formal arrangements. In my work I am committed in traditional quilt patterns and structures. It is a language that we speak together, not a private story. If you know the traditional blocks, you can read the quilts of the 1850s, but you can also read the quilts of the 1960s and of 2025. You can find the blocks and read the messages from women who wrote these visual poems miles away, and after their death.

I love the way that the language of the quilt offers a sense of connection. The patterns and structures are like the vocabulary and grammar. Perhaps this is why I love textiles so much - the way they create a universal language and every once in awhile a new burst of creative energy comes forth just when the form seems dead and stale with no hope for renewal.

The structure is what excites me but it’s also the same thing that made me feel so cynical about piecing and patchwork. The rigidity within the form is what I have to work through just like I had to work through the rigidity of my own mind.

The same thing applies to society more broadly. We question whether there is any hope for freedom and creativity within our rigid public structures. So many of us stand outside it, cynical and judgmental. Others want to tear it down. We can critique it cynically from the sidelines but that is pretty arrogant. Arrogant and missing that we are part of what has become rigid.

One day, I started quilting. I had started therapy the year before and had started working through some of the rigidity and judgmental aspects of my mind. In this process I began to soften and with it I started imagining myself as an artist.

My creative block was broken in an act of faith. I decided to fully embrace my curioity regardless of what I would make. I decided it was going to be amazing.

But how do we have faith in a mess or even a cesspool? Faith and fantasy are not about escape—they are tools for transformation. Fantasy is what allows us to imagine something new inside an existing form, to see beyond what is already established. Without fantasy, we are trapped in what exists; cynicism leaves us there. Faith allows us to trust that within structure—whether in quilting, institutions, or creative practice—there is room for miracles. It’s how we dream new worlds into being.

In my studio trying to figure out how to piece these queens together.

One of my favorite writers, Todd McGowan, believes that fantasy is a key to freedom. He says “…it’s crucial that fantasy must also be part of the solution. It’s a different view than the one that says we need to see things as they really are. I think that’s impossible, and not even a good ideal anyway, to be honest.” What gives our fantasies an ethical edge is “…when we cease regarding it as an escape from our reality and begin to see it as more real than our reality” (McGowan). It’s possible to use fantasy to build stronger communities, not just private palaces.

Faith isn’t just an escape, it is how we build something better. If cynicism leaves us with only what exists, faith allows us to imagine something new within a form.

My goal with quilting is to make something totally new and creative in the old form. I was afraid to be stuck in the muck of what has been already done. I was sure that I would spend hours of my time making something just to find that it come out old and stale. Something stillborn and without life.

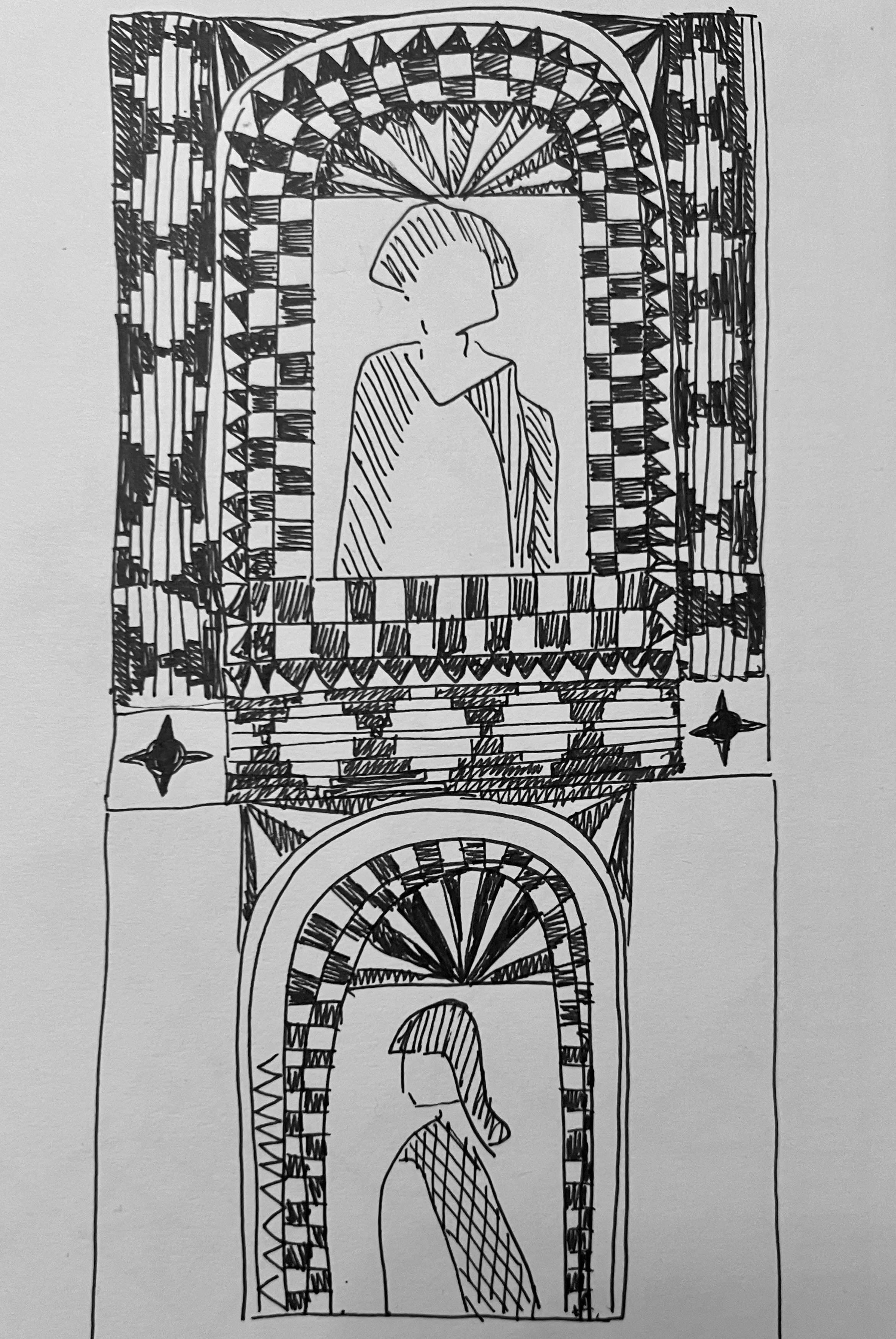

At the Duomo in Genoa

For me it wasn’t enough to make something new that was disconnected from the old forms. I didn’t want to make a completely new kind of art. I wanted to work with the old forms and old language of the quilt. I wanted to be part of the communal, public language. I wanted another quilter to be able to look at what I had made and be able to read the language I was speaking. I wanted it to exist for everyone in that way. A story that could be told around the world.

Years ago, I was traveling through central China with my daughter. One afternoon, feeling particularly far from home and a bit lost, I came across a group of five older women sitting by the side of the path. They were selling knit gifts, talking, and knitting as they waited for customers. I missed my own friends, the familiar rhythms of conversation, and the quiet comfort of making together. I didn’t speak Mandarin, and they didn’t speak English, but I did speak the language of knitting. I gestured toward the work in their hands, and one of the women passed her knitting to me. I recognized the pattern instantly and continued where she had left off. She laughed, surprised, and for a while, we talked in stitches rather than words.

I watched the women talking, their voices overlapping, their hands moving fluidly over their knitting. I understood nothing. The sounds and gestures, the rhythm of their conversation—it all felt closed to me. I could have stayed in that silence, let my foreignness settle in my bones. But instead, I reached for something I understood: the knitting. When one of the women passed me her work, I hesitated, then began stitching the familiar language. For a moment, everything paused. Then, a ripple of surprise, laughter—a spark of recognition. The gap between us had closed, if only for a moment. Faith is, at its core, an act of communion—a belief that meaning can emerge even when the structures that separate us seem immovable. It is the belief that meaning can emerge even when the structure appears rigid or unfamiliar. The shared language of textiles made that moment possible, just as quilting makes it possible for makers across generations to speak to each other through form.

Quilting, like knitting, is communal by nature. It is a conversation, not a monologue. Unlike other forms of art, which can exist as singular visions, quilts have always carried collective histories. They are built from shared patterns, passed-down knowledge, and forms that contain both tradition and reinvention at once. To engage with quilting is to engage with something larger than oneself—to enter a conversation that spans time and space, much like I did that day on the roadside in China.

Fantasy doesn’t have to be about escape — it can be invention. It is what allows us to look at a rigid structure and find a crack, to take what seems fixed and find possibility inside it. Without fantasy, we stay trapped in what already exists. With it, we make something new. The grid of the quilt is like the rhythm of the knit stitch—it provides just enough structure to make improvisation legible, to allow one maker to pick up where another left off. If cynicism isolates us, faith pulls us back into relationship—with history, with community, and with the ongoing work of creation.

Gauche painting (by Sarah Gagnon) of a Two-Sided Quilt: Nine-Block "Log Cabin" Variation Deborah Pettway Young, c. 1960 Cotton twill, print, jersey knit, denim, polyester. This is one of the quilts I spent hours studying to understand the form.

Gauche painting (by Sarah Gagnon) of a Two-Sided Quilt: Nine-Block "Log Cabin" Variation Deborah Pettway Young, c. 1960 Cotton twill, print, jersey knit, denim, polyester. This is one of the quilts I spent hours studying to understand the form.

The Gees Bends quilters innovated in incredible ways with their quilts by using classic quilt blocks. They represent this creativity within the form of quilting better than any other community I’ve encountered. They didn’t burn down what had come before but used the form.

Over the last few years I have been studying the Log Cabin Block inspired by the ways that these quilters broke that block open and created some of the most surprising works of art. I’ve stared at a hundred of these quilts and I’ve made a hundred of my own. To me, what they accomplished with this block is a kind of miracle. Their quilts are impossible. Something that could only be born of faith and fantasy.

I still find myself stuck and unable to solve my creative problems. Last year I started off making a quilt called the Queens quilt which uses a variation of the Log Cabin quilt. For over a year, I stared at fabric that refused to come together. I stitched, unstitched, arranged, rearranged—only to find myself more lost than when I began. It felt like the quilt was resisting me, like no amount of planning could force it into place. In my frustration, I turned to something small—tiny black and white strips of cloth in the courthouse steps variation of the Log Cabin block that I learned from the Gees Bends quilters. They started to form frames around these four queens. Instead of forcing a vision, I felt the structure guide me, hoping that something would take shape.

With this quilt, I am found myself working through ideas of the quilt, but also ideas of myself and my place in society. I’m pulling from every bit of quilting I know, from appliqué to foundation paper piecing and it’s slowly coming together. This is faith in action—not knowing if something will work, but continuing to work. Breakthroughs happen over time; they require persistence and hope that the process may bear fruit.

Sometimes waiting for a miracle takes time. It takes time to conjure up a fantasy. To have the faith to see something that doesn’t exist and is currently impossible. The rigidity doesn’t get broken up overnight and our own rigidity gets in the way. But sometimes we do see a miracle and something new comes forward.

Inside the Duomo in Genoa, Italy, 2024

Faith is not passive belief or blind optimism, but a willingness to step into uncertainty, to work within limitations, and to trust that something meaningful can emerge. Faith resists the easy out of cynicism, which offers the illusion of knowing without the risk of creating. It is the belief that structure is not a cage but a foundation, that tradition is not a burden but a conversation. Faith allows us to see potential where rigidity seems absolute, to imagine something new within the old, and to invest in a form even when we don’t yet see the outcome. It is what moves us from critique to participation, from doubt to making, from isolation to community.

The main cathedral in Genoa seemed like it had called my quilt into existence. When I walked inside I couldn’t believe that I had made a quilt so similar to it in form and color. Not only that, but I had brought it with me to Italy. Of course, my daughter and I just had to do a photoshoot.

Faith and fantasy can’t live in the same world as cynicism and snobbery. I could have stayed in the imaginary worlds of my own mind, creating in isolation, convinced that structure was my enemy. But structure—whether in quilting, in art, or in the institutions we live within—is not what holds us back. It’s our refusal to step toward it, to work within it, to test its possibilities. The real risk isn’t being constrained by form, but missing out on the depth, connection, and creativity that form allows. I didn’t need to burn it all down. I just needed to step inside.